Executive Summary

With the start of the UN Climate Conference talks in Belém, Brazil (COP30), 10-12 November 2025, and the Sharm el-Sheikh Peace Summit to end the war in Gaza, the impact of war on climate change can no longer be ignored, as their greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) contribute significantly to the climate crisis. Military spending was evident in the Gaza war and President Biden’s request to Congress in October 2023 for additional USD 105 billion in funding Israel’s devastating war on Gaza and in support of Ukraine against Russia. This huge funding shifts money away from climate finance, whereby developing countries need USD 387 billion annually to adapt to the impacts of climate change, and only USD 28 billion was made available in 2022. This reflects a severe lack of climate finance and thereby sowing the seeds of mistrust and derailing climate negotiations.

Reporting on armies’ greenhouse gas emissions remains voluntary under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The data is often absent or incomplete, creating a gap in calculating military emissions and environmental impacts before, during, and post conflicts such as dealing with waste or reconstruction.

The urgency of the climate crisis makes it imperative that we close the military emissions gap to meet the Paris Agreement target of 1.5°C. Therefore, governments need to recognize the need to reduce the emissions of their militaries and periodically report on it. Agreeing to bring military emissions to the table of UN climate change conferences would help create momentum and encourage countries to share their best practices in reducing their armies’ emissions, even if reporting on it remains voluntary.

Introduction

In July 2025, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that military activities contribute to climate change, emphasizing that countries must consider emissions from their armed conflicts and have a legal duty to prevent their environmental damage (CEO, 2025).

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), reporting on military emissions is voluntary (under IPCC Category A.5.1) and data are often absent or incomplete, creating a wide gap in reported military emissions. Furthermore, both the UN’s military expenditure forms issued by the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs and the International Energy Agency statistics fail to account for military fuel consumption and energy use.

In 1997, the U.S. government announced that it would only sign the Kyoto Agreement if their military was explicitly exempt from reporting and reducing emissions. Although this exception was lifted in 2015, reporting is still limited and voluntary. Countries with high military spending such as the United States, China, the United Kingdom, Russia, India, and France are among the biggest beneficiaries of this loophole.

According to Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR, 2022), the global military sector is a significant contributor to climate change. Their updated data estimates annual operational emissions at 500 million tons of CO₂ (1.0% of the global total), while the total military carbon footprint reaches 2,750 million tons of CO₂ (5.5% of the global total). These are conservative figures, as they exclude emissions from the impacts of armed conflicts, underscoring the sector’s substantial role in global greenhouse gas emissions.

This report argues that assessing military emissions is critical for climate action, even on a voluntary basis. Such assessments can reduce emissions by sharing best practices and technologies. To this end, states must commit to enhancing the scope, frequency, and transparency of their military emissions reporting. This commitment must be supported by concrete pledges to make meaningful and credible emissions reductions.

Backgrounds & Facts

- It is estimated that the military sector (including industries that produce equipment and weapons) is one of the largest sources of emissions, producing 5.5.% of total global emissions. Nevertheless, countries avoid disclosing these emissions in their national reports (CCPI, 2024).

- The voluntary nature of including military emissions in national climate commitments undermines climate action. This is especially critical as rising military spending leads to a growing gap in unaccounted emissions.

- The annual carbon footprint of British military spending is estimated at around 11 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), an estimate that includes the full life cycle of military activities, equivalent to the annual emissions of 6 million cars (SGR, 2020). However, the Ministry of Defence has officially reported a much lower estimate of around 3.1 million tonnes from 2022 to 2023, as its official reporting tends to omit emissions from military capabilities (such as aircraft and ships) and the broader arms industry linked to it.

- The carbon footprint of the EU military in its last official report in 2019, was estimated at about 24.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), equivalent to the emissions of about 14 million cars. This is a conservative estimate based on available data as the analysis of the Conflict and Environment Observatory indicates that the total military carbon footprint of all EU and NATO countries was around 39 million tonnes of CO2e in 2021, France accounts for about a third of it (CEO, 2021, CCPI, 2024). This discrepancy is due to the low transparency and a lack of comprehensive public reporting on military emissions, which often only accounts for direct emissions rather than the full-life cycle of military emissions.

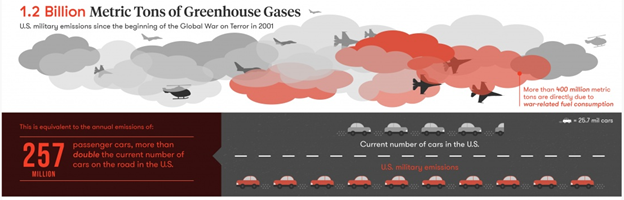

- The U.S. military is the world’s largest institutional emitter of greenhouse gases. The U.S. government has indicated that the U.S. military sector in 2021 emitted 56 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e). However, the Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR, 2022) indicates a much higher number, equivalent to 205 million MtCO2e. As It is shown in the following figure, Between 2001 and 2019, Watson University estimated U.S. Army Emissions at about 1.2 billion Metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (The Watson School of International Public Affairs, 2019). Furthermore, studies suggest that the overall impact is likely to be much higher due to factors such as war and equipment manufacturing and the expansion of military activities, including Military bases, energy, global transport, military training and waste (The University of Utah, 2025).

Source: The Watson School of International Public Affairs, 2019

- Waste management represents approximately 3.2 – 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions (UNFCCC, 2024). Therefore, armies should reduce and responsibly manage their generated waste, such as surplus materials, equipment and ammunitions that are usually destroyed by open detonation or incineration.

- Military training generates significant GHG emissions, particularly in vulnerable environments like semi-arid deserts. The carbon footprint of these exercises is unmeasured, raising serious climate and environmental concerns that must be addressed through regular assessments and mitigation of their negative impacts.

- According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, escalating tensions between powers like the U.S. and China drove global military spending to a new high of USD 2.24 trillion in 2023. This fiscal priority sharply contradicts their ongoing inability to mobilize sufficient funds for climate action and adaptation.

- A recent Transnational Institute (2023) study, “Climate Costs of Military Spending,” reveals that NATO’s commitment to spending 2% of GDP on military affairs will lead to an estimated cumulative total of USD 11.8 trillion by 2028. This figure is enough to fulfill developed countries’ climate finance commitments, yet it will also generate an additional 467 MtCO2e in military emissions.

Analysis of the military emissions gap

Many countries do not accurately report their military sector’s carbon emissions, and the data is often partial and incomplete. Therefore, global military carbon emissions are significantly underreported due to systemic data gaps and misclassification. Emissions from activities like warplanes and arms manufacturing are often categorized under civilian sectors like “aviation” or “industry.” Although fuel use for bases and vehicles is a known contributor, studies of major militaries (e.g., US, UK, EU) show that the majority of emissions stem from underreported supply chains and arms production (SGR, 2022). Emissions from warfare itself are not reported at all.

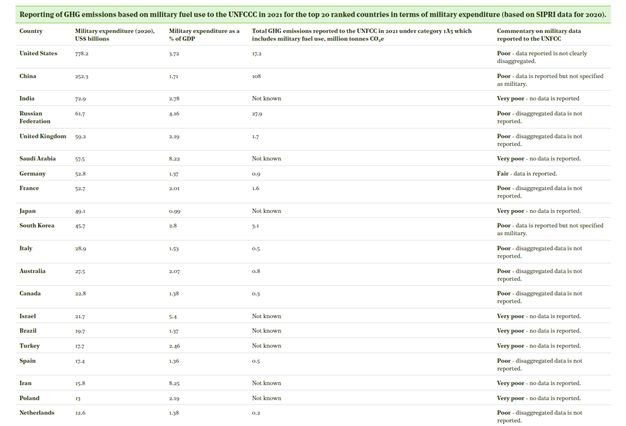

This problem is exacerbated by the UNFCCC’s reporting framework, which only requires data on military fuel consumption. As a result, a large gap exists between official reports and comprehensive estimates of the military carbon footprint, which include military supply chain, number of military personnel, and the ratio of fixed to mobile GHG emissions, as shown in the figure below.

Source: The Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS, 2022)

Thus, there is a significant gap in the reporting of military and war emissions, a gap that is not only hidden to the public, but also to decision-makers and researchers.

Although many military technology companies produce CSR reports and environmental data, the quality of these reports varies widely: a company like Lockheed Martin lists the emissions of its product use, while others provide incomplete data. This discrepancy reflects a parallel gap in military reporting, showing a clear disparity in transparency in this critical sector.

Another dimension of assessing military emissions lies in the commitment to integrate climate considerations into defense planning. This integration is based on four pillars: developing knowledge, adapting military tools and infrastructure, contributing to mitigation efforts, and enhancing national and international cooperation.

Defense ministries in key countries and entities, including NATO (NATO, 2023), the United States (US DOD, 2024), Spain (Publicaciones Defensa, 2023), France (Ministère des Armées, 2022), and the UAE (UAE, 2023), have begun implementing climate adaptation and mitigation plans to reduce their emissions. These efforts are becoming a core part of strategic planning, risk management, and military education to build a more resilient and sustainable defense force. A leading example is NATO’s Climate Change and Security Action Plan, which outlines developing a methodology to measure greenhouse gas emissions that “could contribute to the formulation of voluntary targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the military “. However, more needs to be done to reduce emissions and address other environmental issues. Without losing sight of other environmental issues that need to be addressed when assessing military environmental impacts, these include the procurement and decommissioning of equipment, military supply chain, waste management, and environmental protection during military activities.

Recommendations

Armies cannot manage what they do not measure. This report highlights the importance of the assessment and measurement of military emissions and the impact of this assessment on mitigating emissions and directing climate finance. This assessment also demonstrates that valuing ways of peace, such as those held in Sharm el-Sheikh on October 13, 2025, to end the war in Gaza, is not only a humanitarian imperative but also a vital strategy for reducing the global impacts of climate change.

To close the military emissions gap, countries should:

- Commits to the inclusion of the military as part of greenhouse gas mitigation goals.

- Agree to put military emissions on the table at UN climate change conferences.

- Countries, especially UNFCCC Annex I members, must be obligated to periodically report on military emissions and improve their reporting standards. This commitment must be supported by credible reduction pledges and must focus on the substance and methodology of the reports, not just their submission.

Furthermore, to ensure a level playing field globally, and to maintain the credibility of international pledges, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) must work on updating its standards for military emissions reporting by:

- Establish clear targets to reduce military greenhouse gas emissions, in line with the 1.5°C target set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

- Commit to GHG emission reporting mechanisms that are robust, comparable, transparent, and based on the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories protocol, which are independently verified.

- Set clear goals for armies to conserve energy, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and diversify energy sources by incorporating new and renewable energy.

- Have clear goals to reduce or improve the efficiency of the military technology industry.

- Prioritizing initiatives that reduce emissions at source, rather than relying on greenhouse gas emission offset schemes. In the context of military emissions, these initiatives include peacebuilding and conflict cessation efforts.

- Commit to integrating climate and environmental assessments into the decision-making process for all military activities.

- Highlight the relationship between climate change and environmental degradation and demonstrate a commitment to reducing the overall environmental impact of all military activities and missions.

- Commit to improving military land management to protect land and preserve biodiversity.

- Commit to raising climate and environmental awareness for decision-makers on how militaries can mitigate the impacts climate change and environmental degradation.

- Share information on good military practices with non-military stakeholders.

- Commit to allocating appropriate resources to ensure planning and implementation of mitigation and adaptation policies for armies.