Executive Summary

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is set to become one of the most influential trade policies worldwide, linking climate action to international trade to prevent carbon leakage. For Arab countries with energy and carbon-intensive industries and export sectors reliant on fossil fuels such as aluminum, steel, and fertilizers, the economic consequences could be significant.

Beginning in 2026, exports from the Arab region to the European Union will be subject to significant carbon costs, estimated at 70 to 95 Euros per ton of CO₂ emitted, under the EU’s Emission Trading System (ETS). Should regional industries fail to implement domestic decarbonization reforms and mitigation efforts, the competitiveness of Arab regions in the European market will dwindle.

Beyond economics, CBAM is reshaping Arab negotiations. The CBAM without technological and financial support disregards the well-established concept of common but differentiated responsibilities in climate action. It’s not one size fits all, and that is the basis of the Arab negotiating stance that adopts a pragmatic approach to strategically balance economic development with the imperative to advance decarbonization efforts. Countries like UAE and Morocco, recognize CBAM as a catalyst for industrial transformation and leveraging it to introduce investments in low carbon markets and manufacturing.

This report argues that the EU’s CBAM is imposing significant economic pressure on Arab nations, acting not only as a climate instrument but also as a potential barrier to trade that could constrain Arab exports while favoring EU industrial competitiveness. In response, Arab countries are adopting a dual-path strategy: pragmatically engaging with the tariff structure while actively seeking international support and recognition of their domestic mitigation efforts, such as technical support for Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems and financing for green technology adoption. Furthermore, CBAM is compelling Arab states to accelerate the implementation of their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), explore carbon pricing mechanisms, and consider domestic ETSs as defensive economic measures. Arab countries also need to have a unified front to leverage better diplomacy and strategic bilateral and/or multilateral cooperations in the region.

Introduction

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment (CBAM) marks a turning point in global socioeconomic policy. Under the “Fit for 55” package, The EU introduced a new set of laws designed to reduce greenhouse emissions by at least 55% in 2030 (compared to 1990); imposing for the first time a carbon-based tax/tariff on select imports: aluminum, cement, electricity, hydrogen and steel, based on their embedded emissions (European Commission, 2023). This mechanism is designed to align the carbon cost of imported goods with the EU’s internal carbon pricing, thereby preventing carbon leakage and strengthening incentives for global decarbonization (Zachman et al., 2020). Although this policy will have worldwide repercussions, no region is poised to feel its economic impact more profoundly than the Arab world.

The timing of the EU’s CBAM is particularly sensitive for Arab economies, as it arrives during a critical transition phase. While several Arab countries are taking steps toward establishing voluntary carbon markets, their economies remain heavily dependent on carbon-intensive exports (International Energy Agency, 2023). For example, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) aluminum industry emits 12-16tCO2 per ton of primary aluminum while EU aluminum industry averages 6-8 tCO2 (Arab Monetary Fund, 2023). Compounding this challenge is the widespread absence of domestic carbon pricing mechanisms, leaving regional exporters structurally misaligned with the EU’s climate-driven trade policy. As a result, the new CBAM law poses an economic risk, particularly to the EU’s biggest trading partners: Morocco, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia and UAE. While Arab countries are increasing the ambition of their NDC 3.0, with better MRV tools, institutions, and non-market approach to mitigate their emissions, CBAM is not just functioning as a tariff but an enforcement mechanism, accelerating industrial reforms, and imposing a significant strain on Arab economies.

Facts & Figures

CBAM Timeline and Scope

EU Emission Trading Systems (ETSs) Carbon Price Projections

The price of allowances within the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) establishes a foundational benchmark that indirectly governs the financial impact of CBAM (European Commission, 2023). While CBAM benchmark and certificate costs are directly calculated using the weekly average EU ETS auction price, creating a transparent and dynamic link, the broader ETS price signal exerts deeper, strategic influence (Zhou & Wang, 2023). A higher and volatile ETS price increases the CBAM liability for non-EU producers, amplifying competitive pressure on exporters from regions without equivalent carbon pricing. This dynamic creates a powerful indirect incentive for trading partners to adopt their own carbon pricing or decarbonization measures to reduce exposure. Furthermore, the EU ETS price trajectory signals the EU’s long-term carbon cost expectations, influencing global investment decisions in clean technology and low-carbon production. Consequently, the ETS price does not merely set a numerical tariff under CBAM; it acts as a pivotal economic lever, accelerating global policy alignment and transforming carbon costs into a central factor in international trade and industrial strategy (World Bank, 2023).

The EU ETS carbon prices and their projections are estimated as follows:

- According to the European Commission (2024), the EU ETS Price Range for 2024 is 60-85 Euro/tCO2.

- According to the International Monetary Fund analysts (2024), the projections for EU ETS Price Range for 2030 is 70-95 Euro/tCO2. However, it can be much more or less above that range depending on carbon market conditions.

Arab EU trade

- The European Union ranks among the top three export destinations for Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, Egypt, Bahrain, and Algeria, underscoring a critical economic dependency on the European market.

- Morocco exports more than 1 billion USD/year in fertilizers to the EU.

- GCC aluminum exports (UAE, Bahrain, Qatar) to the EU constitutes 10% of global aluminum trade.

Readiness of Arab countries (Per NDC 3.0)

- ETSs development are underway for GCC countries (World Bank, 2024).

- Egypt and Jordan will soon pilot carbon market in their relative stock trades.

- MRV systems are still fragmented, with only the UAE having the best-case scenario outcome.

- According to UNFCCC NDC synthesis, 60% of Arab NDCs lack detailed industrial mitigation pathways (UNFCCC, 2023).

- Arab NDC’s are ambitious, but skepticism arises on translating this ambition to measurable outcomes.

- There is a measurable risk in Arab countries’ export volumes, whereas without ETSs reforms, 15% to 30% of export volumes could become unviable (IMF, 2023).

- In the pilot phase of NDC implementation, the private sector in the Arab countries highlighted the complexity of the system’s obligations, with those managing multi-tier supply chains reporting particular difficulty in achieving transparent MRV, which is critical for addressing carbon leakage.

Analyzing How the CBAM is Forcing a New Arab Economic Reality

CBAM: The Arab Competitive Edge at Risk

CBAM poses a serious threat to the fossil fuel energy-intensive sector, stripping away its price-based competitiveness. A key vulnerability for most Arab producers is their lack of certified low-carbon alternatives or the technical knowledge required for reliable emissions measurement.

CBAM presents a sweeping challenge to key industrial sectors across the Arab world, threatening to erode long-held competitive advantages. In the aluminum industry, where the UAE and Bahrain collectively account for nearly 10% of global trade, reliance on cheap fossil fuel energy remains prevalent despite the UAE’s regional leadership in diversifying its energy mix. This dependency means both nations will be significantly impacted, facing a projected 8–15% cost increase without rapid decarbonization (World Bank, 2025).

Beyond aluminum, the fertilizer sector in the Arab countries is under growing pressure. Producers in Morocco and Egypt, who still largely depend on conventional methods, find themselves at a disadvantage as EU competitors transition to green ammonia (World Bank, 2025). To remain viable, these producers must urgently shift their feedstock, or risk being left behind. Likewise, the steel and cement industries confront a direct threat to their price competitiveness. CBAM will recalibrate the market, making Arab products less competitive against Turkish, European, and potentially lower-cost Indian imports. Across all these sectors, a common vulnerability exacerbates the risk: many producers lack either certified low-carbon alternatives or the technical expertise to accurately measure their emissions, leaving them acutely exposed to the mechanism’s financial penalties. Without a swift and strategic pivot toward greener production, a vital pillar of the Arab regional economy risks declining competitiveness.

CBAM: a Forcing Mechanism

The EU’s CBAM is emerging as a powerful external catalyst, fundamentally altering Arab economies. More than a simple tariff, CBAM represents a structural force compelling regional policy reform by making the adoption of carbon pricing an urgent financial imperative for the first time. This is accelerating a pivotal shift within the region, particularly among the hydrocarbon-rich GCC countries, which are now fast-tracking domestic Emissions Trading Systems (ETS). These systems are viewed not merely as compliance tools but as strategic engines to generate revenue for financing the green transition, provided these funds are rigorously earmarked for sustainable green projects and not absorbed into general budgets.

However, a critical bottleneck threatens to undermine these efforts: the widespread lack of robust Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) frameworks. With the notable exception of the UAE, most Arab states lack the institutional capacity and technical tools for consistent, transparent emissions accounting. While recent NDC 3.0 process submissions from key players like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Morocco show enhanced ambition, translating pledges into verifiable action requires substantial, statewide investments in monitoring infrastructure and institutional strengthening (UNFCCC, 2024).

Ultimately, CBAM’s most immediate impact is at the industrial level, where it is directly pushing Arab producers toward greener production pathways. In sectors from petrochemicals to steel, the mechanism is forcing a technological reckoning, incentivizing investments in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), pioneering green hydrogen projects, and the pursuit of lower-carbon alternatives in historically emission-intensive processes (IRENA, 2022, 2023). This external pressure is effectively accelerating a necessary but complex industrial transformation, tying the region’s future export competitiveness directly to its success in decarbonization.

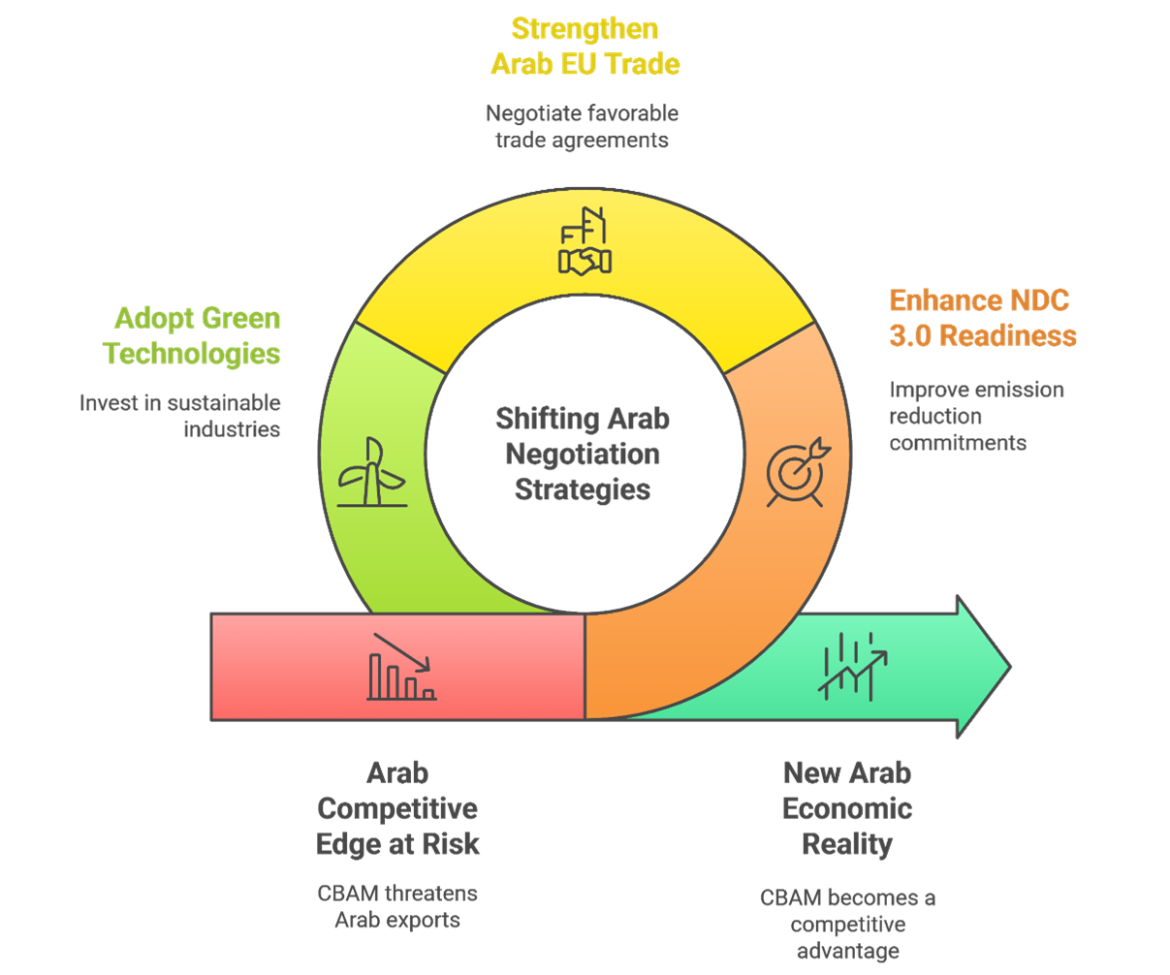

Shifting Arab Negotiation Strategies

The new CBAM policies are compelling a pragmatic shift in the Arab world, following a historical stance of resistance to external green mandates. This resistance, justifiably rooted in a principle of climate justice: as nations with minimal historical responsibility for cumulative global emissions, many Arab states long viewed stringent climate policy as an inequitable burden. Now, however, CBAM has made alignment with EU standards an economic necessity. Arab countries are consequently steering their industrial transitions through strategic investments in technology and climate financing, reframing the mechanism not merely as a penalty but as a broader climate-finance obligation. They are leveraging compliance to demand greater access to advanced technology and co-financing, aiming to build the cleaner supply chains the EU requires.

In the broader scheme, CBAM is accelerating a global reallocation of investment away from high-carbon regions. This could paradoxically benefit some Arab countries with unique export profiles to the EU, attracting capital for green industrialization. Ultimately, the next decade presents a critical race: Arab nations must rapidly industrialize along sustainable pathways or face severe market exclusion, navigating the tension between their limited historical responsibility and the urgent present-day demands of the global low-carbon transition.

Outlook and Policy Recommendation

With the introduction of CBAM, the first “carbon tax” as it is called. Carbon intensity will be as vital as trade cost and quality, marking the first step to broader introduction of tax systems/direct policies against high carbon-intense sectors. CBAM transcends a mere tariff, creating a structural bridge between trade and climate action. By responding with a coherent strategy, Arab nations can convert this challenge into a catalyst, reshaping their economic competitiveness and amplifying their diplomatic voice in the climate era.

Arab countries now face a critical strategic navigation: they must decarbonize their carbon-intensive sectors or risk gradual exclusion from key markets in favor of greener competitors. This imperative is reshaping regional economic diplomacy, positioning climate policy not as a peripheral concern but as a central determinant of trade access and future growth. Success in this new landscape requires a nuanced and branched approach, leveraging negotiations to link mitigation commitments to guaranteed technology transfer and co-financing, while actively engaging with global carbon markets to turn compliance costs into opportunities.

Early movers, such as the UAE and Morocco, are already adopting this strategic posture, positioning themselves as future green exporters and seeking to lock in long-term advantages within the European market. For others, the lag in developing a coherent strategy, one that combines diplomatic pressure for equitable technology access with domestic carbon pricing mechanisms, carries the severe risk of de-integration from evolving global supply chains and demand. Ultimately, the trajectory for each nation will be defined by its ability to transform the CBAM framework from a unilateral penalty into a negotiated pathway for investment, innovation, and sustained market relevance.

To navigate the challenges and leverage the opportunities presented by the EU CBAM, Arab nations should adopt a proactive and coordinated strategic agenda. The following recommendations outline a pathway to transform CBAM from a compliance burden into a catalyst for sustainable industrial modernization and enhanced diplomatic influence.

1. Forge a Unified Regional Negotiating Position

Move beyond fragmented national responses by developing a cohesive Arab stance on CBAM. A unified strategy, potentially spearheaded by the GCC and integrating supply-chain partners in the Levant and North Africa, would amplify negotiating power. This collective position could serve as a model, influencing climate policy coordination across Africa and Central Asia and ensuring the region’s interests are effectively represented in international forums.

2. Link Climate Action to Equitable Finance and Technology Access

Frame the decarbonization imperative within the broader principle of climate justice. In negotiations, Arab countries should explicitly tie their mitigation conditional commitments to guaranteed access to climate finance, green technology transfer, and capacity-building support from the EU. The argument is one of shared responsibility, as key energy suppliers to Europe, the region’s rapid transition requires commensurate investment to ensure energy security and prevent supply chain disruption.

3. Advocate for Differentiated Transition Timelines for Critical Industries

Negotiate for pragmatic, sector-specific transitional measures for hard-to-abate industries like aluminum, steel, and petrochemicals. Recognizing the technical complexity and capital intensity of overhauling these deep-rooted supply chains, a phased compliance timeline is essential. This allows for a managed transition that safeguards economic stability while pursuing definitive decarbonization pathways.

4. Proactively Implement Domestic Carbon Pricing Mechanisms

Accelerate the development of robust domestic carbon pricing, such as ETS, as mandated in upcoming NDCs. Governments should proactively introduce incentives and support for industries and institutions to adapt, ensuring these markets are functional and effective tools for reducing emissions before being fully integrated into the CBAM framework.

5. Fast-Track Institutional Capacity in MRV and Carbon Markets

Prioritize significant investment in building regional capacity for Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) and ETS administration. With the UAE currently leading, a concerted effort is needed to elevate capabilities across all Arab states. This includes developing transparent monitoring frameworks, training technical experts, and establishing credible regulatory institutions as the essential foundation for any effective carbon reduction strategy and for validating progress under CBAM.

References

Arab Monetary Fund. (2023). Industrial competitiveness and export structures in Arab economies. Arab Monetary Fund.

European Commission. (2023). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) regulation and guidance documents. https://ec.europa.eu

European Commission. (2024). EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS): Current rules and market data. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en

European Commission. (2023). Fit for 55: Delivering the EU’s 2030 climate target.

https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en

International Energy Agency. (2023). Energy technology perspectives 2023: Low-carbon industrial pathways. International Energy Agency.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). Fiscal policies for a low-carbon economy: Carbon pricing, markets, and international coordination. International Monetary Fund.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). Global carbon pricing update 2024.

International Monetary Fund.

International Renewable Energy Agency. (2022). Green hydrogen supply in Africa and the Middle East. International Renewable Energy Agency.

International Renewable Energy Agency. (2023). Renewable energy prospects in the Arab region. International Renewable Energy Agency.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2023). NDC synthesis report 2023. UNFCCC Secretariat.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2024). NDC registry (interim).

UNFCCC Secretariat. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/NDCStaging/Pages/Home.aspx

World Bank. (2023). State and trends of carbon pricing 2023.

World Bank Group. https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org

World Bank. (2024). MENA economic update: Green industrial transformation and trade implications. World Bank Group.

World Bank. (2025). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) exposure indices methodological note. World Bank Group.

Zachmann, G., Roth, A., & Tamara, S. (2020). Preparing for a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Bruegel Policy Contribution 2020/15. https://www.bruegel.org

Zhou, H., & Wang, S. (2023). Global supply-chain impacts of the EU CBAM: A multi-regional input–output analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 421, 134827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.134827