The 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30)

Belém, Brazil, 10-22 November 2025

Analysis of Key Outcomes

“To accelerate implementation, we need a coalition of the willing. We need a whole-of-society approach. Our countries are not able to implement the commitments made here without the private sector, the investors, the subnational governments and all our societies.”

Executive Summary

The 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) in Belém, Brazil, was set to be a pivotal “COP of Implementation,” in the heart of the Amazon a decade after the Paris Agreement. Under the spirit of “Mutirão”, a Brazilian term for collective action.

COP30 was the second-largest on record, with over 56,000 registered delegates, underscoring its high stakes. However, this significance was matched by profound challenges. The conference was characterized by deeply entrenched divisions between developed and developing countries, logistical hurdles including a temporary evacuation due to a fire, and a struggle to convert the spirit of Mutirão into concrete, consensus-driven outcomes on the most contentious issues.

While the conference successfully delivered a landmark agreement on tropical forests and operationalized key financial mechanisms, it ultimately fell short of the transformational breakthrough many had hoped for. Key negotiations on fossil fuels, carbon markets, and the Global Goal on Adaptation were deferred or diluted, leaving a legacy of both significant progress and unresolved tensions that will heavily shape the road to COP31 in Antalya, Türkiye.

COP30 attendance and its significance

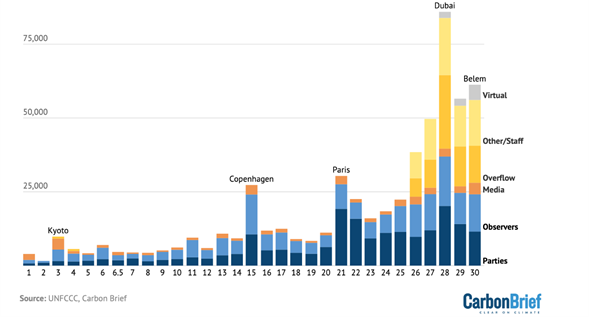

COP30 had 56,118 registered delegates, second-largest COP after COP28 in Dubai. However, this number does not deliver an accurate picture of representation because in terms of party delegates, COP30 was attended by 11,519 party delegates, the fourth largest behind the past 3 previous COPs in Dubai, Baku and Egypt respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Final COP attendance figures COPs 1-30 (Carbon Brief, Nov 2025)

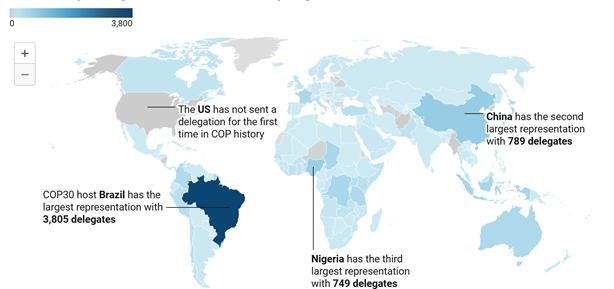

Around 57 heads of state and government attended, including leaders from Europe, French President Macron, the UK prime Minister, and China’s Vice Premier. However, for the first time in the history of COPs, the United States was “officially” absent. This followed Donald Trump speech at the UN general assembly in September 2025 that the climate crisis was “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world”, a “green scam” based on “predictions … made by stupid people”, confirming his absence from COP30.

The largest national delegations came from Brazil (3,805), China, Nigeria, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Figure 2). The significant presence of these countries, combined with over 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists (one in every 25 attendees), underscored the influence of the fossil fuel and critical minerals industries and led to the predicted deadlock in the fossil fuel deal, as this report’s findings will show.

Figure 2: Delegates by country registered to COP30 (Carbon Brief, Nov 2025)

Key Successes and Landmark Agreements

Despite the challenges, COP30 secured several notable achievements that include:

The Belém Pact: A defining outcome of the conference, this landmark agreement formally links tropical forest conservation with climate finance. It establishes a new verification and funding mechanism, recognizing the critical role of forests, particularly the Amazon, Congo, and Mekong basins, as global climate assets and creating a structured pathway to reward their protection.

Operationalization of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG): Parties finalized the Baku-to-Belém Roadmap to implement the new climate finance goal. The roadmap outlines a trajectory to scale climate finance to $1.3 trillion per year by 2035, with a specific target to triple adaptation finance for developing nations by 2035. The plan emphasizes specific allocations for adaptation and loss and damage and crucially integrates a focus on mobilizing private finance.

Loss and Damage Fund Secured: The Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage, operationalized at COP29, saw significant progress in Belém. Parties secured initial pledges totaling $12 billion and, critically, agreed to streamline access procedures for the most vulnerable countries, moving from pledges to actionable support.

Procedural and Governance Milestones

Gender Action Plan: Adoption of a new Gender Action Plan to mainstream gender equality across climate actions.

Future Hosts: An arrangement was confirmed for Türkiye to host COP31 in partnership with Australia for a shared Presidency. Ethiopia was confirmed as the host for COP32, which will be the first time a Least Developed Country (LDC) hosts the conference.

Challenges and Contentious Divisions

The vision of Mutirão was tested by persistent and familiar blocks, which prevented consensus on several critical issues.

Fossil Fuel Language: The most significant failure was the inability to secure an agreement on “phasing out” fossil fuels. Intense opposition from the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) and the Arab Group, who emphasized “energy security” and development rights, led to a watered-down outcome. The final text merely calls for “accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels in a just and equitable manner,” mirroring the vague language from previous COPs, particularly COP28 in Dubai, and failing to provide a clear, time-bound agreement.

Deadlock over Article 6 (Carbon Markets): For the second consecutive year, negotiations on key aspects of international carbon markets under Article 6 collapsed. Parties could not agree on rules for Article 6.2 (cooperative market agreements) or 6.4 (centralized crediting mechanism), deferring all major decisions to COP31. This ongoing uncertainty undermines the integrity and scalability of voluntary and compliance carbon markets.

Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA): While COP30 accepted a final decision with a consolidated set of adaptation indicators, the outcome was weak. There was no agreement on new finance indicators, and many developing countries expressed concern over the “clarity” and potential burden of the proposed indicators. The African Group, in particular, opposed indicators that track domestic budget allocations, arguing they shift the responsibility for adaptation finance from developed to developing nations.

Article 9.1 and the Climate Finance Debate: The fundamental rift over climate finance persisted. The G-77/China bloc, supported by the African Group and LMDCs, pushed relentlessly to separate Article 9.1, the legal obligation of developed countries to provide finance, as a standalone agenda item and to secure a tripling of adaptation finance. Developed countries, including the EU and Canada, resisted this, preferring to discuss finance in its entirety, including voluntary and private contributions. This stalemate reflects a deep-seated lack of trust and divergent interpretations of historical responsibility.

The Brazilian Presidency Roadmaps and Unresolved Issues

The Brazilian Presidency employed a multi-track strategy, conducting high-level ministerial consultations, technical negotiations, and overarching “Mutirão” consultations on cross-cutting issues. However, this approach could not overcome core political disagreements.

In response to the deadlock on fossil fuels and deforestation within the formal negotiations, COP30 President Corrêa do Lago announced the creation of two non-negotiated “Presidency Roadmaps.” These are intended to maintain political momentum on:

The transition away from fossil fuels in a just and equitable manner.

Halting and reversing deforestation by 2030. The effectiveness of this voluntary initiative will be tested at COP31, where outcomes are to be reported.

Major Unresolved for COP31

Fossil Fuel Phase-Out: The core debate over ending fossil fuel use remains entirely open.

Article 6 Carbon Markets: All key decisions on accounting, integrity, and oversight of carbon markets were deferred.

Technology Transfer: Parties failed to agree on conclusions for the joint report of the Technology Mechanism, stalling progress on this critical enabler of action.

Adaptation Indicators: The GGA indicator framework requires further refinement and political buy-in, with finance remaining a central point of contention.

Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP): Discussions continued, with no major decision, but debates highlighted divisions over unilateral trade measures and the role of fossil fuels in development.

Financing Gaps: Despite the NCQG roadmap, firm commitments from developed nations currently cover only about 40% of the annual target, highlighting a significant delivery gap.

Conclusion

COP30 originally set to be a COP of truth and consensus, will be remembered as a conference of contrasts. It achieved historic, targeted successes on forests and finance architecture, as expected from the Brazilian presidency, demonstrating that multilateral progress is still possible. However, it also laid bare the severe limitations of the consensus-based UN process when confronting the core drivers of the climate crisis, fossil fuels, and the entrenched inequities over finance and responsibility. The Brazilian Presidency’s Mutirão vision fostered dialogue but could not forge a full consensus. The legacy of COP30 is a heavy and urgent agenda for COP31 in Türkiye, where the world will see if the “just and equitable transition” can be defined with the specificity and ambition the climate crisis demands.